Start learning about restorative justice, its origins, and the different forms it can take. You will also get referrals to other resources that offer deeper and more thorough information about restorative justice.

Steps 1A: Youth Criminalization and 1B: People Harmed described how punitive responses to harm enacted by the criminal legal system perpetuate racial and ethnic disparities and fail to meet the needs of people harmed. Young people who have caused harm and had their cases processed through the criminal legal system are calling for an alternative. Their families and communities have called for another path. People harmed also seek an alternative path to justice, healing, and accountability. Restorative justice has the potential to respond to all of these calls.

There are both indigenous and western roots to restorative justice, and as the movement grounds itself in truth and liberation for all, both of these roots should be recognized and explored. Restorative justice in the United States can be traced back to Indigenous origins. Although examples of what many have termed “restorative justice” among First Nations communities in Canada have been well documented, less has been written about equivalents in the US. Part of the difficulty in tracing restorative justice back to specific practices within Indigenous communities is that they do not typically hold “restorative justice” as a program or a model, but rather as part of their lives and embedded in their culture. “Restorative justice” is a Western term. Moreover, the Indigenous roots are not monolithic—Indigenous communities practice circles and justice in different ways. Part of honoring this work means we must stay humble, knowing that these practices came before us and will outlast us. We must also stay grounded in the practice of constant learning and unlearning.

At its core, restorative justice is about relationships, how you create them, maintain them, and mend them. It is based on the philosophy that we are all interconnected, that we live in relationship with one another, and that our actions impact each other. Grounded in this idea of interconnectedness, restorative justice is able to provide an alternative way of addressing wrongdoing. Wrongdoing is seen as a damaged relationship, a wound in the community, a tear in the web of relationships. Because we are all interconnected, a wrongdoing ripples out to disrupt the whole web—a harm to one is a harm to all. To learn more, watch the What is Restorative Justice? webinar led by the Restorative Justice Project (formerly housed at Impact Justice).

Restorative justice offers guidance on how to respond when wrongdoing occurs. The focus on punishment within the US criminal legal system typically does not serve to heal the person harmed or provide space for genuine accountability and growth for the person who caused the harm. Restorative justice shifts the paradigm of our current systems by making a radical commitment to meeting the needs of those harmed, those who caused harm, and community members. The restorative justice process allows for all their voices and needs to be heard. Howard Zehr, renowned internationally for his seminal thinking and writing about the Western concept of restorative justice, defines restorative justice as:

an approach to achieving justice that involves, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense or harm to collectively identify and address harms, needs, and obligations in order to heal and put things as right as possible.

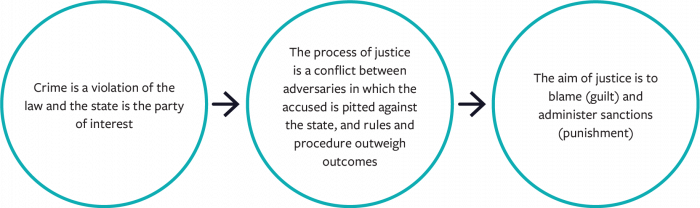

Zehr speaks and writes about changing lenses when comparing the criminal legal system with restorative justice:

When harm occurs, the current criminal legal system asks:

In contrast, restorative justice asks:

Three additional questions restorative justice asks in order to identify the path forward:

Restorative justice as a paradigm shift provides value far beyond simply being an alternative to criminalization and incarceration. In the final report of the Zehr Institute’s Restorative Justice Listening Project, restorative justice is referred to as a movement that “embodies a relational justice lifestyle that invites people to live-right, do-right, and make-right through human connection and community for the sake of the ‘common good.’” It asks us to shift from holding power ‘over’ others to holding power ‘with’ them, as well as believing in each person’s capacity to best know their needs and honor their agency. This shift allows for the redistribution of concentrated power from an individual towards the collective. In this way, restorative justice can seek healing and accountability not only at the personal level, but also at the structural levels of society. Addressing structural harms can include both present injustices and the legacy of historical harms.

The Little Book of Restorative Justice is a fantastic resource for learning about restorative justice. A short video below by Brave New Films called Restorative Justice: Why Do We Need it? also provides an overview of restorative justice in relation to the criminal legal system.

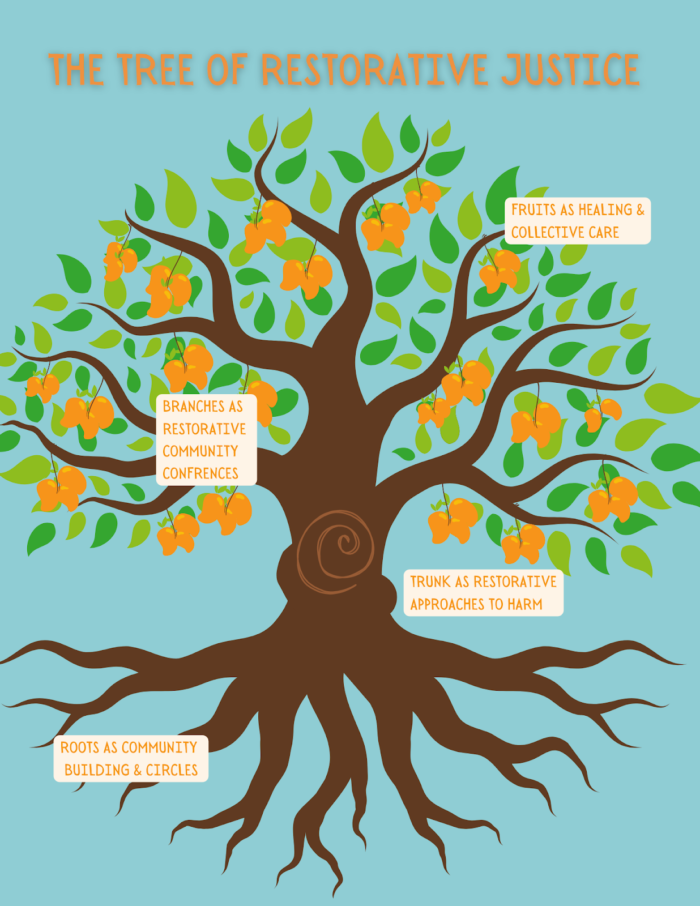

There are many different types of restorative justice processes that allow families, schools, and communities to practice restorative justice in a variety of contexts, to promote community building, to respond to harm, to create community-held plans for accountability and healing, and to practice collective care. We like to think of this as all belonging to a Tree of RJ.

“Maybe you are searching among the branches for what only appears in the roots.”

Rumi

“A tree with strong roots can withstand the most violent storm, but the tree can’t grow roots just as the storm appears on the horizon”

The Dalai Lama

Community is the root of our tree of restorative justice. How we relate to one another determines how we respond to harm when interpersonal harm is inevitably caused. Circles are a ceremonial and intentional way of gathering where everyone is respected, folks get a chance to speak and listen from the heart, and stories are shared and valued. Circles can be used to make collaborative decisions, address conflict, celebrate achievements, and for many other purposes. Key elements of a circle process are ceremony, community guidelines, a talking piece, the presence of a circle keeper or facilitator, and consensus decision-making. For more graphics and handouts explaining the circle process, please visit the Living Justice Press site. Additionally there are many excellent films about restorative justice and circles, such as Circles, about restorative justice in Oakland; Hollow Water, about how restorative justice helped the Ojibwe indigenous community in Canada heal from a legacy of sexual abuse, and a short video below, Restorative Justice in Oakland Schools: Tier 1. Community Building Circle, that demonstrates a circle process led by Oakland youth.

Restorative Justice in Oakland Schools- Tier One. Community Building Circle from Stories Matter Media on Vimeo.

Restorative justice practitioners and community circle keepers can explore questions such as – what does it mean to be a neighbor? What do we love about our community? How can we take care of each other? What are actions we can take to strengthen this community?

Ultimately, when we build a strong community that recognizes our interconnectedness we are better able to build towards collective wellness and are better prepared to heal together and to take accountability together. The focus on community and relationship also allows us to more deeply understand and address structural harm and oppression.

Community circle keeping, alongside other community-building practices, creates a deep network system of roots that builds trees strong enough to weather storms. In other words, it weaves a social fabric that is resilient enough to hold all of the things that happen within the community.

“Trees, for example, carry the memory of rainfall. In their rings we read ancient weather – storms, sunlight, and temperatures, the growing season of centuries. A forest shares a history, which each tree remembers even after it has been felled.”

Anne Michaels

“Our scars are like the rings in a tree trunk, showing its progress through life. How we heal and move forward through adversity… this is what makes the difference.”

Morgan Rhodes

If community circles and relating restoratively to each other are the tree roots, then there are many restorative approaches used to respond to harm that can be found in the tree trunk. There are many tools, frameworks, and strategies that can be used when working with people impacted by harm to identify and explore strategies to meet needs and support accountability and healing.

Just as the passage of time is marked in a tree trunk by concentric circles called annual growth rings, cultivating and practicing restorative approaches to harm within community can be called upon again and again when conflict and harm occur. Rings can not only tell us how old a tree is but also what the weather was like during each year of the tree’s life- in this way, the impacts of harm aren’t forgotten even as a tree continues to form new cells and continues to grow.

A tree trunk can also be marked on the outside by rivets, indentations, and even large knots, which are called burls. Tree burls are caused when the tree undergoes some type of significant stress. On our tree of restorative justice, a burl can represent how a community can respond when more serious harm occurs – a tree will create this outgrowth in order to allow the rest of the tree to continue growing normally. More intensive restorative approaches to harm can be utilized, again not to minimize or disappear the harm or its impacts, but to respond in a way that acknowledges both the harm and the humanity of everyone involved.

Even through hard winters and incidents of significant stress, a community tree can continue to grow through a trunk that responds creatively, empathetically, and restoratively.

“Sometimes our fate resembles a fruit tree in winter. Who would think that these branches would turn green again and blossom, but we hope it, we know it.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“Let me look upward into the branches of the flowering oak and know that it grew great and strong because it grew slowly and well.”

Bill Vaughan

When a community has deep relationship-building roots and a sturdy trunk represented by resiliency and experience in responding to harm and supporting people impacted by it, then branches can begin to extend. The branches on our tree of restorative justice are represented by Restorative Community Conferences (RCCs). RCCs are an intentional and intensive facilitated process of bringing people together impacted by an incident of harm, including persons harmed, persons who have caused harm, individuals to support each of them, and community members. This process seeks to identify, repair, and prevent harm through supporting meaningful accountability and healing.

Just as branches and their leaves provide shade, RCCs create restorative and healing plans that provide comfort and refuge. Similar to the tree canopy where branches can grow off of one another, RCC facilitators and participants become experienced community members who are able to share their lived experience and create a network that can show up for future restorative justice processes.

Family Group Conferencing (FGC) is the basis of the RCC model you will learn about in this toolkit and is originally from Aotearoa (Aotearoa is the Māori word for the land now known as New Zealand). The FGC model brings together a young person who caused a harm, their caregivers/family, the person(s) they harmed, and others (e.g., the police, a social worker, youth advocate, etc.) to discuss how to help the young person take accountability and learn from their mistakes. During the FGC, participants agree on a plan through which the youth can make up for harm they caused. The plan becomes legally binding, and the Department of Child, Youth and Family Services monitors the young person to ensure they complete the plan. Step 1E: The Evidence outlines the history and effects of Family Group Conferencing in Aotearoa. The Little Book of Family Group Conferences: New Zealand Style provides an in-depth exploration of how FGCs work in New Zealand. The documentary Restoring Hope offers a close look at FGCs as it follows a Māori restorative justice facilitator in Aotearoa who facilitates conferences with people harmed, those responsible, their caregivers/family, and community members.

The Restorative Justice Project honors and values restorative justice in all of its many flavors and models. We’re intentional about the parameters and processes of the RJD model because of our core elements (which you will learn more about in the following Step 1D: Restorative Justice Diversion) and the results we have found from RCCs (which you will learn more about in Step 1E: The Evidence).

“Life without love is like a tree without blossoms or fruit.”

Khalil Gibran

“Be a helpful friend, and you will become a green tree with always new fruit, always deeper journeys into love.”

Rumi

When all other parts of a tree – the roots, trunk, and branches – have found a way to support each other and weather storms, then the fruits of restorative justice can bloom. This nourishing fruit can look like healing journeys and accountability practices on an individual, family, neighborhood, and community level.

It also looks like a culture of collective care, showing up with love and care for one another. Collective care views the well being of community members as a shared responsibility of the group.Together a community can work towards collective empowerment, joint accountability, and dismantling oppression.

Fruits bring us the sweetness of life and are a joyful reason to gather and share. Even fruits that fall to the ground and are never picked for eat, they go back into the earth and provide nourishment to the soil and the root systems of the tree. In this way, our healing journeys and collective care bring us together and strengthen our communities.

LEARN about restorative justice through reading this section and accessing other resources

WATCH the webinar What is Restorative Justice? by the Restorative Justice Project

WATCH Restorative Justice in Oakland Schools: Tier 1. Community Building Circle and the other films listed above